Now that China is portraying itself as a global peacemaker, taking credit for encouraging Iran and Saudi Arabia to restore their diplomatic relations, will ending the war in Ukraine be next? One year to the day after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the PRC Foreign Ministry issued a position paper on “the Political Settlement of the Ukraine crisis.” At a time when China has faced criticism for considering providing lethal aid to Russia and when Xi Jinping—just reinstated as president for a third term—is planning a trip to Moscow for his 40th meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, followed by a virtual meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, the Foreign Ministry document seeks to position China as a potential mediator. Zelensky had long sought a meeting with Xi, to no avail.

Widely dismissed as a rehash of previous positions with little new content or intent to pressure Russia to withdraw its forces or reach a negotiated settlement, the 12-point paper actually reveals quite a bit about China’s priorities in the conflict and broader foreign policy goals. Above all, China aims to prevent its fence-sitting from damaging its reputation in the Global South, but the document also points to vulnerabilities that preoccupy Chinese officials in the event of a future conflict.

With respect to Iran and Saudi Arabia, China facilitated what the two countries sought themselves to achieve and served as the closer, following extensive diplomacy by Iraq and Oman. In Ukraine, neither side is prepared to seek a political settlement in the absence of territorial gains. What we see clearly in both cases, however, is how China uses diplomacy to promote its own interests— in the case of Iran and Saudi Arabia, preventing enmity between two key energy partners from interrupting crucial flows of oil and gas—and, in Ukraine, protecting China’s global reputation from further erosion, its security from nuclear threats and its economy from disruption.

Respecting the sovereignty of all countries

Here, China repeats an oft-stated point on the need to follow the principles of the UN Charter and observe the territorial integrity, independence, and sovereignty of all states, regardless of size, and without double standards. At first glance, this seems to be inherently contradictory, as the UN itself has stated that Russia’s war on Ukraine violates the UN Charter. However, China is not speaking about Ukraine in this first point—indeed Ukraine is not mentioned in it; rather, this is an appeal to the Global South, where China hopes to use its own regional security initiatives to counter US influence. This point restates most of the principles in China’s Global Security Initiative, issued three days before the position paper on Ukraine.

No Cold War

This is a reiteration of points originally made in the February 4, 2022, Sino-Russian joint statement, where China sides with Russia on questions of European security and blames the US and its allies for creating insecurity. What is interesting here is that China is positioning itself to play a role in developing European security architecture and in ensuring the stability of Eurasia.

Ceasing hostilities

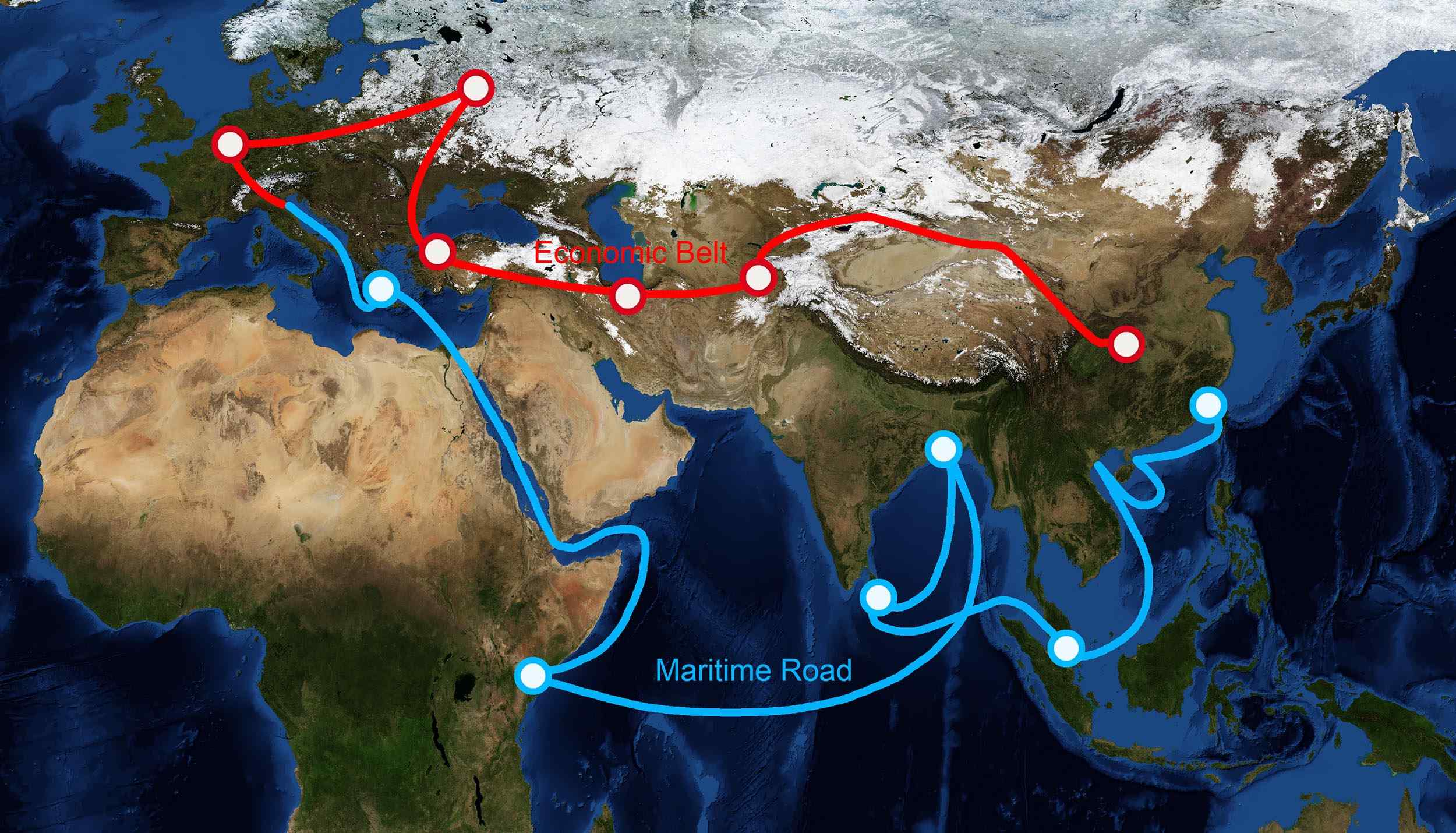

No one benefits from conflict and war, the position paper states, and particularly not China, which has seen interruptions to the Belt and Road Initiative, its trade with Ukraine plummet, and its reputation in Europe fall to a new low.

Resuming peace talks

China claims to seek a constructive role here, but urging a political settlement as soon as possible effectively seeks to lock in Russia’s territorial gains and represents an effort to prevent a Russian defeat. Moreover, unlike India’s prime minister, Xi Jinping has never publicly urged Putin to choose peace.

Resolving the humanitarian crisis

Despite its tacit support for Russia, China has provided limited humanitarian aid to Ukraine. However, PRC officials emphasize the need for neutrality and impartiality in providing aid and urge the UN to play the leading role.

Protecting civilians and prisoners of war

Previous PRC statements have expressed concern over civilian casualties. PRC officials undoubtedly remain concerned about their own citizens who remain in Ukraine. As of late 2022, nearly 200 PRC nationals still in Ukraine were seeking to leave, following a delayed exit by some 6,000 after the start of the war. At least one PRC national was shot while attempting to flee eastern Ukraine in early 2022.

Safeguarding nuclear power plants

On March 9, 2023, the PRC announced it would contribute 200,000 euros to the International Atomic Energy Agency to ensure the safety of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant—the largest nuclear power plant in Europe and the 10th largest in the world—and a target of Russian shelling. PRC officials began highlighting the importance of safeguarding nuclear power plants in August 2022, after Russian shelling temporarily disconnected Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant from the national grid. PRC concern for nuclear safety in Ukraine reflects the importance of the issue for European countries, many of which have become disillusioned by China’s tacit support for Russia in Ukraine. Moreover, as the PRC prepares to boost the share of nuclear power from 5 percent of the country’s energy to 15 percent by 2050, Chinese officials are seeking to create a norm against targeting civilian plants in case of future conflict.

Reducing strategic risks

In keeping with its own no-first-use policy, PRC officials have spoken out in meetings with Western officials against nuclear threats and nuclear use. This appears to be China’s only red line on Ukraine, though no Chinese statement, including this one, has ever called out Russia specifically for making such threats in Ukraine.

Facilitating grain exports

This is important for China for several reasons. Higher food prices for developing countries are one of the key effects of the Russian war on Ukraine—and an issue for China as it positions itself as a champion of the Global South. Wang Yi’s food security initiative at the July 2022 G-20 meeting was an effort to display concern about this, despite China’s tacit support for Russia. China has faced its own losses—it no longer receives the modest quantity of corn it previously imported from Ukraine and saw Russian forces destroy Mariupol, where COFCO, a PRC state-owned agribusiness group, had invested in grain transshipment in Mariupol.

Opposing unilateral sanctions

This is a longstanding PRC position, although the Chinese government retaliates economically against states that pursue policies on Taiwan and human rights issues that are at odds with PRC interests. In the context of Ukraine, opposition to sanctions is equivalent to rhetorical support for Russia.

Keeping industrial and supply chains stable

This is increasingly a concern for Chinese officials given ongoing efforts by the United States and other countries to reduce economic dependence on China and China’s access to dual-use technologies.

Promoting post-conflict reconstruction

China is positioning itself to play a key role in the reconstruction of a postwar Ukraine. According to reporting from Nikkei Asia, a simulation by the Academy of Military Sciences, a People’s Liberation Army think tank, projects Russian victory by summer, assuming the Republican-controlled US House of Representatives halts assistance. Once the war ends, Ukraine will need massive investment in reconstruction.. Realizing this, Ukrainian officials have avoided calling out PRC positions on the war, although some Ukrainian experts foresee a recalibration of the relationship with China as likely in the future because of China’s tacit support for Russia.

The Chinese leadership has yet to engage in any meaningful diplomacy on Ukraine and this statement reads more like a damage-limitation strategy than a call to action. Although Xi values the Sino-Russian partnership in part because it provides support for his country’s goal to play a bigger role in global and regional governance, in the case of Ukraine, China’s “pro-Russian neutrality” has sidelined China from playing a meaningful diplomatic role in the most significant challenge to European security in 30 years.

Another version of this article was published on China Resource Risk, Elizabeth Wishnick’ s blog.