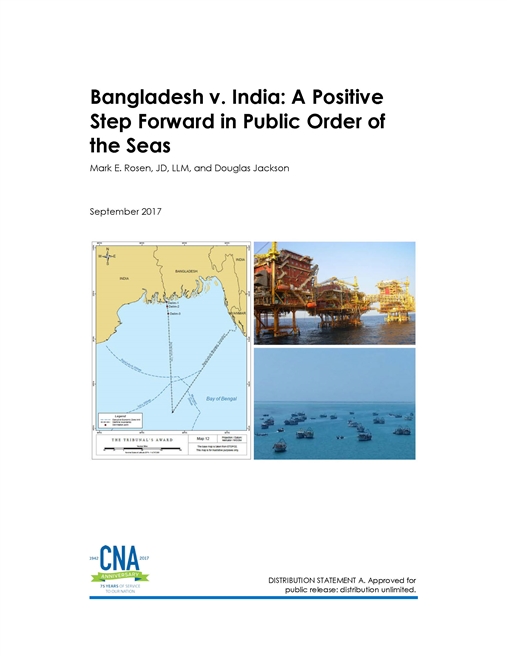

In 2014, a tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague, Netherlands, delivered its decision resolving a decades-old dispute between India and Bangladesh, “regarding the delimitation of the maritime boundary between them in the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf within and beyond 200 nm in the Bay of Bengal.” Even though this decision is not new, it is appropriate to make a detailed examination of this case in light of a significant amount of litigation in the boundary dispute arena; most notably, the arbitration decision involving China and the Philippines that was decided in July 2016.

Background

The dispute dates back to the partition of India in 1947, when the Bengal Boundary Commission first established the border between India and Bangladesh (then East Pakistan). In the early 1970s, a feature (low tide elevation) emerged in the mouth of the river separating the two countries (called New Moore by India and South Talpatty by Bangladesh), which led to competing territorial claims and contributed to the continuation of tensions over the maritime boundary. Growing interest in oil and gas reserves in the Bay of Bengal heightened the stakes for resolving maritime boundary disputes between Bangladesh and its neighbors. These stakes were underscored in 2006, when India included over 15,000 square kilometers of ocean territory claimed by Bangladesh in oil and gas blocks it had put up for bid.

Tensions ratcheted up further in 2008 following separate incidents a month apart. In November, two ships from Myanmar’s navy accompanied four survey ships from Korean company Daewoo into disputed waters, leading Bangladesh to dispatch three naval vessels to the area to halt exploration and defend its sovereignty. In December, Bangladesh’s navy again responded when an Indian survey ship, at the time reportedly accompanied by two Indian naval vessels, also entered disputed waters. Bangladesh initiated arbitration proceedings under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) against each country in 2009.

Assessment

Contrary to the view by many observers that India “lost” the case in The Hague, the result was quite equitable; each side was able to claim victories and has accepted the ruling. The Award provided Bangladesh with additional territory, but India retained a greater proportion of EEZ than Bangladesh relative to the ratio of their relevant coastlines, a standard measure of whether the delimitation of a maritime boundary is equitable. Although the tribunal rejected India’s argument that the low-tide elevation that sparked the dispute should be a base point in calculating the maritime boundary, the tribunal awarded to India the area containing it, which may also contain oil and gas deposits. The tribunal rejected Bangladesh’s argument that the impact of climate change on its coastline constituted a “special circumstance” to deviate from the standard equidistance method of delimiting territorial seas, thereby avoiding the creation of a precedent or the opening up of past decisions to appeal.

Download reportDISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. PUBLIC RELEASE. 9/5/2017

Details

- Pages: 84

- Document Number: DOP-2017-U-016081-Final

- Publication Date: 9/5/2017