The Change Healthcare cyberattack that rocked the healthcare system for the past month is certainly the most serious case of medical ransomware yet. A survey of nearly 1,000 hospitals by the American Hospital Association earlier this month found that 94 percent of hospitals were financially affected when the claims processor’s network was crippled, with more than half reporting “significant or serious” impact. But the Change Healthcare attack is far from the only cyberattack to hit U.S. hospitals—nor is it likely to be the last.

Hackers are targeting the healthcare sector with increasing frequency. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, large breaches jumped 93 percent from 2018 to 2022, especially ransomware attacks. The Federal Bureau of Investigation received more reports of ransomware attacks on the healthcare and public health sector in 2022 than on any other critical infrastructure sector, and the number of attacks has risen since then. In a 2023 survey by the Ponemon Institute, 88 percent of healthcare organizations reported experiencing at least one cyberattack in the prior year. A November 2023 cyberattack on Ardent Health Services, a 30-hospital health system, forced hospitals in three states to reroute ambulances to other hospitals. And earlier this year, Lurie Children’s Hospital, the largest pediatric facility in Chicago, had to delay scheduled procedures when it detected a ransomware attack and proactively shut down several of its information technology systems.

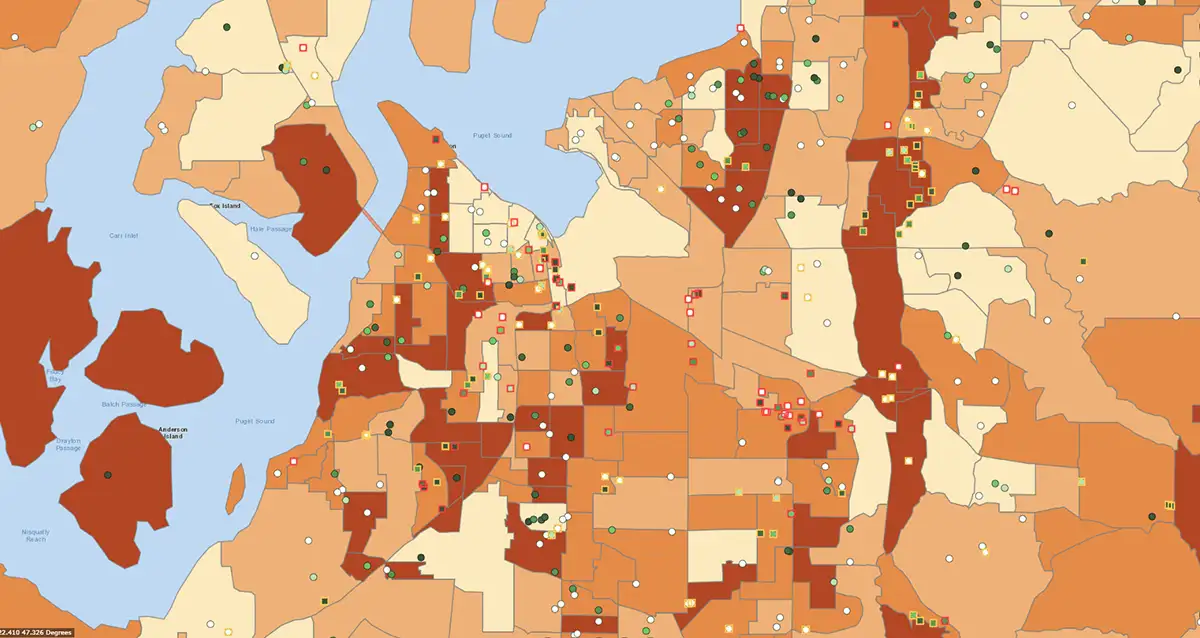

Unfortunately, many hospitals remain vulnerable to these increasingly persistent threats. Hospital cyber capacity and capabilities vary widely, which complicates the development and implementation of cyber standards. In addition, hospitals have a large attack surface, made up of a series of interconnected systems such as electronic health records, remote patient monitoring technology, imaging equipment, and telemedicine platforms. Each additional system increases their vulnerability to cyberattack. And partner organizations and vendors—like Change Healthcare—add yet another source of cyber disruption.

Health and Financial Impacts of Hospital Ransomware

Ransomware can threaten lives in hospitals. It can disrupt care, force patients to be rerouted to other hospitals, and delay medical tests and procedures. In addition, when hospital staff have no access to electronic health records and rely on manual recordkeeping, they are more likely to make mistakes that can affect medical outcomes. For example, in 2022, a 3-year-old patient was reportedly given a “megadose” of an opioid pain medication because the hospital’s computer systems were down. Organizations that have experienced ransomware attacks self-report an increase in delays for procedures and tests, longer hospital stays for patients, an increase in complications, and an increase in mortality.

Ransomware attacks also add financial burdens on hospitals that can even be ruinous. A 2023 study found that the cost for a single healthcare data breach averaged nearly $11 million, up 53 percent since 2020. Last year, St. Margaret’s Health in Spring Valley, Illinois, reportedly became the first hospital to shut down permanently in part because of costs associated with a ransomware attack.

Building Cyber Resilience Among Hospitals

Federal regulators have pushed the healthcare industry to improve cybersecurity, and a few agencies offer cybersecurity guidelines and resources for hospitals. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) recently released new voluntary guidelines for hospitals that range from basic cyber hygiene to advanced encryption standards. Similarly, HHS put forward a cybersecurity strategy for the healthcare sector that laid out several goals, including the development of voluntary guidelines and expanding and maturing their “one-stop shop” for healthcare cybersecurity.

Though such preventative measures could protect against most attacks, hospital managers will still need to develop response plans for possible cyber disruptions. All hospitals are already required to have emergency operations plans that address “all hazards,” but those plans are often ineffective at responding to the unique challenges of a cyber incident. Many planners have not documented information-sharing processes or anticipated an environment of degraded communications. In addition, continuity of operations plans often do not cover the cascading effects of a cyberattack, and stakeholders are not fully aware of how cyber insurance—if they have it—will affect their response.

Hospitals will need support in this process. Through our experience helping cities, counties, states, and military services develop cyber incident response plans and run cyber exercises, we have developed a multi-step approach to planning for potential cyberattacks that hospitals should consider:

- An examination of potential cyber threats and levels of disruption—from minor inconveniences to a complete disruption of operations

- A thorough review of the hospital’s mission-critical functions and the people, tools, facilities, and systems needed to accomplish those functions

- Criteria for making major decisions, such as shutting down information systems, remaining open or diverting patients, and transitioning to alternative processes

- Contingency plans for how to keep operations running in the absence of business-critical systems such as phone, email, and electronic files

- Internal and external communication plans, including important contacts in case internal address books are unavailable

- Response plans specific to when partners—including key vendors, nearby hospitals, or local government—are disabled by a cyberattack

A complete and exercised cyber incident response plan will not make the threat of ransomware attacks disappear, but a timely, thorough response can lessen the impact. When Lurie Children’s Hospital detected a cyber intrusion, its staff preemptively shut down phones, email, electronic health records, and the MyChart patient portal to protect their data. Speedy decisions allowed the hospital to keep its doors open, even if some non-emergency services were temporarily affected. Preparing for the worst is hospitals’ best hope of ensuring that the worst never happens.