The aim of this report is to propose additional policy options that the United States might pursue in the South China Sea. It begins with a detailed recounting of existing U.S. policy toward the South China Sea, and concludes by recommending additional policy approaches aimed toward generating a more peaceful, stable, non- confrontational, law abiding environment in the South China Sea. It also addresses U.S. interests, a legal assessment of sovereignty claims, and a primer on the “rules” embodied in international law that Washington wants all parties to follow.

What are the issues?

Competing claims to sovereignty

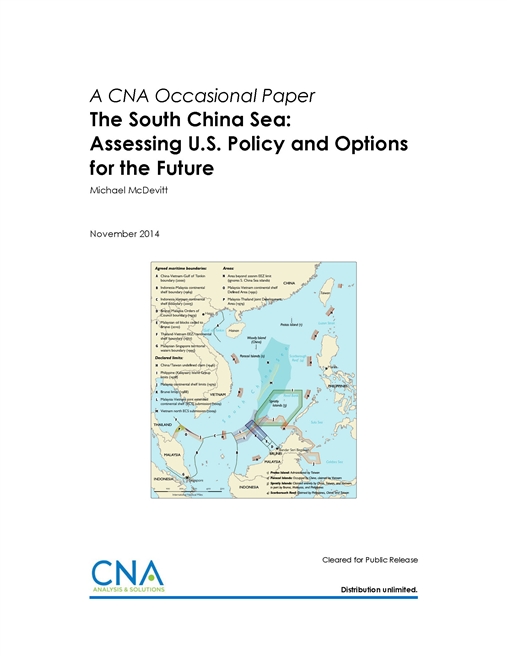

In the South China Sea there are approximately 180 features above water at high tide.1 These rocks, shoals, sandbanks, reefs and cays, plus additional unnamed shoals and submerged features are distributed among four geographically different areas of that sea. These are claimed in whole or in part by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei. China and Taiwan (the Republic of China) claim all of the land features in the South China Sea.

The problem of the nine-dash line (NDL)

This knotty sovereignty issue is greatly exacerbated by the “nine-dash line” that appears on all China’s maps of the South China Sea (SCS), and incorporates about 80 percent of the SCS. Over the past several years, Chinese actions have strongly suggested that the line is much more than a way to depict China’s claims to the land features—it is an attempt to claim China has “historic rights” to a significant portion of the resources that, under the Law of the Sea, legitimately belong to the coastal states. This apparent attempt to rewrite “commonly accepted” international law has resulted in a number of incidents with its SCS neighbors.

China’s behavior in attempting to resolve its claims

China’s approach in the South China Sea is “peacefully coercive.” It is very effective. It has been characterized as a “salami slice” strategy: it continues to take small, incremental steps that are not likely to provoke a military response from any of the other claimants, but over time gradually change the status-quo regarding disputed claims in its favor.

The bilateral issue: U.S. military operations in China’s EEZ

Washington argues that UNCLOS permits nations to exercise “high seas freedoms,” which include, inter alia, peaceful military operations, in the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of coastal states. China disagrees. It claims that these are not peaceful activities. This disagreement has resulted in two serious incidents: the 2001 mid-air collision between a U.S. Navy surveillance aircraft (EP-3) and an intercepting Chinese navy fighter, and the 2009 episode in which Chinese fishermen and paramilitary ships harassed USNS Impeccable. More recently, a dangerously close intercept of a U.S. Navy P-8 maritime patrol aircraft created another diplomatic dustup.

The reality on the ground for U.S. policy-makers

China has control of all the land features in the South China Sea north of 12 degrees north latitude—essentially the northern portion of the South China Sea.

- It has controlled the Paracel Islands since 1974, and, despite Vietnam’s claim, is unlikely to ever leave.

- China effectively resolved the dispute with the Philippines over Scarborough Shoal in 2012 when it established control over the shoal. Again, it is unlikely to relinquish it.

- This means that the Spratly Islands are the only remaining features that are not completely under the physical control of Beijing (or of greater China).

This situation suggests that U.S. policy options, aimed at a peaceful rules-based outcome, need to focus on the Spratlys, which, unfortunately for those who must craft and execute policy, are the most complex and legally arcane area of the South China Sea.

Download reportUnlimited distribution permission granted by Smith Richardson Foundation, Inc. Specific authority contracting number: SRF Grant #2014-0047. Distribution authority is controlled by Smith Richardson Foundation, Inc.

Details

- Pages: 110

- Document Number: IOP-2014-U-009109

- Publication Date: 11/1/2014