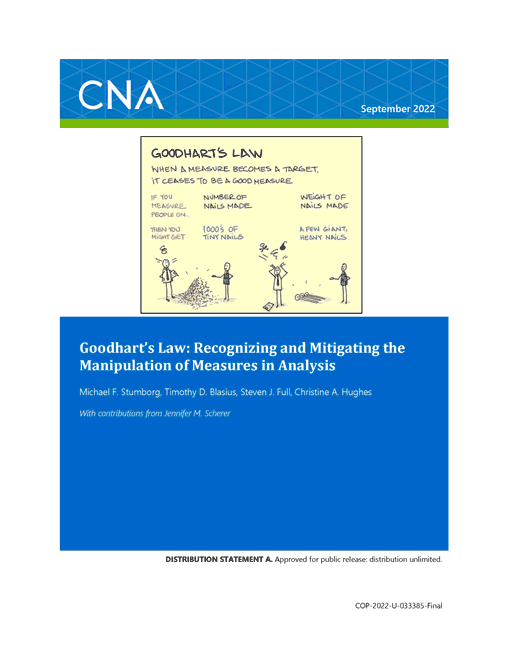

Goodhart's Law

Goodhart’s Law states that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” In other words, when we use a measure to reward performance, we provide an incentive to manipulate the measure in order to receive the reward. This can sometimes result in actions that actually reduce the effectiveness of the measured system while paradoxically improving the measurement of system performance.

Illustrative examples of Goodhart’s Law include the experience of British officials in colonial India. They offered a bounty on cobra skins to reduce the cobra population, only to have entrepreneurial citizens actually breed cobras for their skins and then turn them loose when their fraud was discovered, thus increasing, rather than decreasing, the cobra population.

Goodhart’s Law in Defense Analysis

Examples of Goodhart’s Law abound in defense analysis. They include manipulated measures of performance as diverse as body counts in Vietnam, modern day fighter aircraft readiness rates, and the use-it-or-lose-it “rule” in Department of Defense program management.

The manipulation of measures resulting from Goodhart’s Law is pervasive because direct measures of effectiveness (MOEs), which are more difficult to manipulate, are also more difficult to measure, and sometimes simply impossible to define and quantify. As a result, analysts must often settle for measures of performance (MOPs) that correlate to the desired effect of the MOE. MOEs are difficult to measure and difficult to manipulate. MOPs are easier to measure, but also easier to manipulate. Thus, the negative impacts of Goodhart’s Law are commonplace.

Recommendations to reduce the impact of Goodhart’s Law

These negative effects can sometimes be avoided. When they cannot, they can be identified, mitigated, and even reversed. Analysts, and the organizations that employ them, often in partnership with the customer organizations that receive their analytical products, can take concrete actions to avoid or mitigate the negative effects of Goodhart’s Law. This report recommends that analysts do the following:

- Use MOEs instead of MOPs whenever practicable and possible

- Use the scientific method to generate new measurement data, rather than harvesting existing and possibly compromised data

- Help customers establish authoritative and difficult-to-manipulate definitions for measures

- Identify and avoid the use of manipulated data and data prone to manipulation

- Use measurement data not generated by the organization being measured

- Collect data secretly or after a measurable activity has already occurred

- Measure all relevant system characteristics rather than just a representative few

- Randomize the measures used over time

- Wargame or red team potential measures

This report recommends that the organizations that employ analysts should do the following:

- Return to the roots of operational research to focus more on direct measurements in the field

- Answer the questions that should be answered, rather than the questions that can be answered simply because the required data are already available

- Train analysts on MOEs, MOPs, and Goodhart’s Law and how they are interrelated

- Make recognition of Goodhart’s Law part of the internal peer review process and part f all delivered analytical products

- Identify and share mitigation best practices

Organizations that use data and develop measures that have consequences—both positive and negative—for the persons, organizations, and processes they are charged with measuring and improving should act on these recommendations to identify, understand, avoid, mitigate, or reverse the effects of Goodhart’s Law.

Implementing these recommendations will benefit individual analysts, the organizations that employ them, and the organizations that they support. Admittedly, these recommendations constitute additional burdens on project managers already stressed by limited budgets and tight schedules. Because the negative outcomes of not assuming these burdens will not occur until a future date, they may go unrecognized, or it may be tempting to dismiss them if recognized. Therefore, institutionalizing these additional actions by including them in an already required process (such as peer review) is essential to avoid the pervasive and pernicious effects of Goodhart’s Law.

Download reportDISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited.

Details

- Pages: 40

- Document Number: COP-2022-U-033385-Final

- Publication Date: 9/1/2022